| |

The sculpture and painting of ancient India have recently been rehabilitated

with a surprising suddenness in the eyes of a more cultivated European

criticism in the course of that rapid opening of the Western mind

to the value of oriental thought and creation which is one of the

most significant signs of a change that is yet only in its beginning.

There have even been here and there minds of a fine perception and

profound originality who have seen in a return to the ancient and

persistent freedom of oriental art, its refusal to be shackled or

debased by an imitative realism, its fidelity to the true theory

of art as an inspired interpretation of the deeper soul values of

existence lifted beyond servitude to the outsides of Nature, the

right way to the regeneration and liberation of the aesthetic and

creative mind of Europe. And actually, although much of Western

art runs still along the old grooves, much too of its most original

recent creation has elements or a guiding direction which brings

it nearer to the Eastern mentality and understanding. It might then

be possible for us to leave it at that and wait for time to deepen

this new vision and vindicate more fully the truth and greatness

of the art of India.

But we are concerned not only with the critical estimation of our

art by Europe, but much more nearly with the evil effect of the

earlier depreciation on the Indian mind which has been for a long

time side-tracked off its true road by a foreign, an anglicised

education and, as a result, vulgarised and falsified by the loss

of its own true centre, because this hampers and retards a sound

and living revival of artistic taste and culture and stands in the

way of a new age of creation. It was only a few years ago that the

mind of educated India—“educated” without an atom of real culture—accepted

contentedly the vulgar English estimate of our sculpture and painting

as undeveloped inferior art or even a mass of monstrous and abortive

miscreation, and though that has passed and there is a great change,

there is still very common a heavy weight of secondhand occidental

notions, a bluntness or absolute lacking of aesthetic taste,*

a failure to appreciate, and one still comes sometimes across a

strain of blatantly anglicised criticism which depreciates all that

is in the Indian manner and praises only what is consistent with

Western canons. And the old style of European criticism continues

to have some weight with us, because the lack of aesthetic or indeed

of any real cultural training in our present system of education

makes us ignorant and undiscriminating receptacles, so that we are

ready to take the considered opinions of competent critics like

Okakura or Mr. Laurence Binyon and the rash scribblings of journalists

of the type of Mr. Archer, who write without authority because in

these things they have neither taste nor knowledge, as of equal

importance and the latter even attract a greater attention. It is

still necessary therefore to reiterate things which, however obvious

to a trained or sensitive aesthetic intelligence, are not yet familiar

to the average mind still untutored or habituated to a system of

false weights and values. The work of recovering a true and inward

understanding of ourselves—our past and our present self and from

that our future—is only in its commencement for the majority of

our people.

To appreciate our own artistic past at its right value we have to

free ourselves from all subjection to a foreign outlook and see

our sculpture and painting, as I have already suggested about our

architecture, in the light of its own profound intention and greatness

of spirit. When we so look at it, we shall be able to see that the

sculpture of ancient and mediaeval India claims its place on the

very highest levels of artistic achievement. I do not know where

we shall find a sculptural art of a more profound intention, a greater

spirit, a more consistent skill of achievement. Inferior work there

is, work that fails or succeeds only partially, but take it in its

whole, in the long persistence of its excellence, in the number

of its masterpieces, in the power with which it renders the soul

and the mind of a people, and we shall be tempted to go further

and claim for it a first place. The art of sculpture has indeed

flourished supremely only in ancient countries where it was conceived

against its natural background and support, a great architecture.

Egypt, Greece, India take the premier rank in this kind of creation.

Mediaeval and modern Europe produced nothing of the same mastery,

abundance and amplitude, while on the contrary in painting later

Europe has done much and richly and with a prolonged and constantly

renewed inspiration. The difference arises from the different kind

of mentality required by the two arts. The material in which we

work makes its own peculiar demand on the creative spirit, lays

down its own natural conditions, as Ruskin has pointed out in a

different connection, and the art of making in stone or bronze calls

for a cast of mind which the ancients had and the moderns have not

or have had only in rare individuals, an artistic mind not too rapidly

mobile and self-indulgent, not too much mastered by its own personality

and emotion and the touches that excite and pass, but founded rather

on some great basis of assured thought and vision, stable in temperament,

fixed in its imagination on things that are firm and enduring. One

cannot trifle with ease in these sterner materials, one cannot even

for long or with safety indulge in them in mere grace and external

beauty or the more superficial, mobile and lightly attractive motives.

The aesthetic self-indulgence which the soul of colour permits and

even invites, the attraction of the mobile play of life to which

line of brush, pen or pencil gives latitude, are here forbidden

or, if to some extent achieved, only within a line of restraint

to cross which is perilous and soon fatal. Here grand or profound

motives are called for, a more or less penetrating spiritual vision

or some sense of things eternal to base the creation. The sculptural

art is static, self-contained, necessarily firm, noble or severe

and demands an aesthetic spirit capable of these qualities. A certain

mobility of life and mastering grace of line can come in upon this

basis, but if it entirely replaces the original dharma of the material,

that means that the spirit of the statuette has come into the statue

and we may be sure of an approaching decadence. Hellenic sculpture

following this line passed from the greatness of Phidias through

the soft self-indulgence of Praxiteles to its decline. A later Europe

has failed for the most part in sculpture, in spite of some great

work by individuals, an Angelo or a Rodin, because it played externally

with stone and bronze, took them as a medium for the representation

of life and could not find a sufficient basis of profound vision

or spiritual motive. In Egypt and in India, on the contrary, sculpture

preserved its power of successful creation through several great

ages. The earliest recently discovered work in India dates back

to the fifth century B.C.and is already fully evolved with an evident

history of consummate previous creation behind it, and the latest

work of some high value comes down to within a few centuries from

our own time. An assured history of two millenniums of accomplished

sculptural creation is a rare and significant fact in the life of

a people.

This greatness and continuity of Indian sculpture is due to the

close connection between the religious and philosophical and the

aesthetic mind of the people. Its survival into times not far from

us was possible because of the survival of the cast of the antique

mind in that philosophy and religion, a mind familiar with eternal

things, capable of cosmic vision, having its roots of thought and

seeing in the profundities of the soul, in the most intimate, pregnant

and abiding experiences of the human spirit. The spirit of this

greatness is indeed at the opposite pole to the perfection within

limits, the lucid nobility or the vital fineness and physical grace

of Hellenic creation in stone. And since the favourite trick of

Mr. Archer and his kind is to throw the Hellenic ideal constantly

in our face, as if sculpture must be either governed by the Greek

standard or worthless, it is as well to take note of the meaning

of the difference. The earlier and more archaic Greek style had

indeed something in it which looks like a reminiscent touch of a

first creative origin from Egypt and the Orient, but there is already

there the governing conception which determined the Greek aesthesis

and has dominated the later mind of Europe, the will to combine

some kind of expression of an inner truth with an idealising imitation

of external Nature. The brilliance, beauty and nobility of the work

which was accomplished, was a very great and perfect thing, but

it is idle to maintain that that is the sole possible method or

the one permanent and natural law of artistic creation. Its highest

greatness subsisted only so long—and it was not for very long—as

a certain satisfying balance was struck and constantly maintained

between a fine, but not very subtle, opulent or profound spiritual

suggestion and an outward physical harmony of nobility and grace.

A later work achieved a brief miracle of vital suggestion and sensuous

physical grace with a certain power of expressing the spirit of

beauty in the mould of the senses; but this once done, there was

no more to see or create. For the curious turn which impels at the

present day the modern mind to return to spiritual vision through

a fiction of exaggerated realism which is really a pressure upon

the form of things to yield the secret of the spirit in life and

matter, was not open to the classic temperament and intelligence.

And it is surely time for us to see, as is now by many admitted,

that an acknowledgment of the greatness of Greek art in its own

province ought not to prevent the plain perception of the rather

strait and narrow bounds of that province. What Greek sculpture

expressed was fine, gracious and noble, but what it did not express

and could not by the limitations of its canon hope to attempt, was

considerable, was immense in possibility, was that spiritual depth

and extension which the human mind needs for its larger and deeper

self-experience. And just this is the greatness of Indian sculpture

that it expresses in stone and bronze what the Greek aesthetic mind

could not conceive or express and embodies it with a profound understanding

of its right conditions and a native perfection.

The more ancient sculptural art of India embodies in visible form

what the Upanishads threw out into inspired thought and the Mahabharata

and Ramayana portrayed by the word in life. This sculpture like

the architecture springs from spiritual realisation, and what it

creates and expresses at its greatest is the spirit in form, the

soul in body, this or that living soul power in the divine or the

human, the universal and cosmic individualised in suggestion but

not lost in individuality, the impersonal supporting a not too insistent

play of personality, the abiding moments of the eternal, the presence,

the idea, the power, the calm or potent delight of the spirit in

its actions and creations. And over all the art something of this

intention broods and persists and is suggested even where it does

not dominate the mind of the sculptor. And therefore as in the architecture

so in the sculpture, we have to bring a different mind to this work,

a different capacity of vision and response, we have to go deeper

into ourselves to see than in the more outwardly imaginative art

of Europe. The Olympian gods of Phidias are magnified and uplifted

human beings saved from a too human limitation by a certain divine

calm of impersonality or universalised quality, divine type, guna;

in other work we see heroes, athletes, feminine incarnations of

beauty, calm and restrained embodiments of idea, action or emotion

in the idealised beauty of the human figure. The gods of Indian

sculpture are cosmic beings, embodiments of some great spiritual

power, spiritual idea and action, inmost psychic significance, the

human form a vehicle of this soul meaning, its outward means of

self-expression; everything in the figure, every opportunity it

gives, the face, the hands, the posture of the limbs, the poise

and turn of the body, every accessory, has to be made instinct with

the inner meaning, help it to emerge, carry out the rhythm of the

total suggestion, and on the other hand everything is suppressed

which would defeat this end, especially all that would mean an insistence

on the merely vital or physical, outward or obvious suggestions

of the human figure. Not the ideal physical or emotional beauty,

but the utmost spiritual beauty or significance of which the human

form is capable, is the aim of this kind of creation. The divine

self in us is its theme, the body made a form of the soul is its

idea and its secret. And therefore in front of this art it is not

enough to look at it and respond with the aesthetic eye and the

imagination, but we must look also into the form for what it carries

and even through and behind it to pursue the profound suggestion

it gives into its own infinite. The religious or hieratic side of

Indian sculpture is intimately connected with the spiritual experiences

of Indian meditation and adoration,—those deep things of our self-discovery

which our critic calls contemptuously Yogic hallucinations,—soul

realisation is its method of creation and soul realisation must

be the way of our response and understanding. And even with the

figures of human beings or groups it is still a like inner aim and

vision which governs the labour of the sculptor. The statue of a

king or a saint is not meant merely to give the idea of a king or

saint or to portray some dramatic action or to be a character portrait

in stone, but to embody rather a soul state or experience or deeper

soul quality, as for instance, not the outward emotion, but the

inner soul-side of rapt ecstasy of adoration and God-vision in the

saint or the devotee before the presence of the worshipped deity.

This is the character of the task the Indian sculptor set before

his effort and it is according to his success in that and not by

the absence of something else, some quality or some intention foreign

to his mind and contrary to his design, that we have to judge of

his achievement and his labour.

Once we admit this standard, it is impossible to speak too highly

of the profound intelligence of its conditions which was developed

in Indian sculpture, of the skill with which its task was treated

or of the consummate grandeur and beauty of its masterpieces. Take

the great Buddhas—not the Gandharan, but the divine figures or groups

in cave cathedral or temple, the best of the later southern bronzes

of which there is a remarkable collection of plates in Mr. Gangoly's

book on that subject, the Kalasanhara image, the Natarajas. No greater

or finer work, whether in conception or execution, has been done

by the human hand and its greatness is increased by obeying a spiritualised

aesthetic vision. The figure of the Buddha achieves the expression

of the infinite in a finite image, and that is surely no mean or

barbaric achievement, to embody the illimitable calm of Nirvana

in a human form and visage. The Kalasanhara Shiva is supreme not

only by the majesty, power, calmly forceful control, dignity and

kingship of existence which the whole spirit and pose of the figure

visibly incarnates,—that is only half or less than half its achievement,—but

much more by the concentrated divine passion of the spiritual overcoming

of time and existence which the artist has succeeded in putting

into eye and brow and mouth and every feature and has subtly supported

by the contained suggestion, not emotional, but spiritual, of every

part of the body of the godhead and the rhythm of his meaning which

he has poured through the whole unity of this creation. Or what

of the marvellous genius and skill in the treatment of the cosmic

movement and delight of the dance of Shiva, the success with which

the posture of every limb is made to bring out the rhythm of the

significance, the rapturous intensity and abandon of the movement

itself and yet the just restraint in the intensity of motion, the

subtle variation of each element of the single theme in the seizing

idea of these master sculptors? Image after image in the great temples

or saved from the wreck of time shows the same grand traditional

art and the genius which worked in that tradition and its many styles,

the profound and firmly grasped spiritual idea, the consistent expression

of it in every curve, line and mass, in hand and limb, in suggestive

pose, in expressive rhythm,—it is an art which, understood in its

own spirit, need fear no comparison with any other, ancient or modern,

Hellenic or Egyptian, of the near or the far East or of the West

in any of its creative ages. This sculpture passed through many

changes, a more ancient art of extraordinary grandeur and epic power

uplifted by the same spirit as reigned in the Vedic and Vedantic

seers and in the epic poets, a later Puranic turn towards grace

and beauty and rapture and an outburst of lyric ecstasy and movement,

and last a rapid and vacant decadence; but throughout all the second

period too the depth and greatness of sculptural motive supports

and vivifies the work and in the very turn towards decadence something

of it often remains to redeem from complete debasement, emptiness

or insignificance.

Let us see then what is the value of the objections made to the

spirit and style of Indian sculpture. This is the burden of the

objurgations of the devil's advocate that his self-bound European

mind finds the whole thing barbaric, meaningless, uncouth, strange,

bizarre, the work of a distorted imagination labouring mid a nightmare

of unlovely unrealities. Now there is in the total of what survives

to us work that is less inspired or even work that is bad, exaggerated,

forced or clumsy, the production of mechanic artificers mingled

with the creation of great nameless artists, and an eye that does

not understand the sense, the first conditions of the work, the

mind of the race or its type of aesthesis, may well fail to distinguish

between good and inferior execution, decadent work and the work

of the great hands and the great eras. But applied as a general

description the criticism is itself grotesque and distorted and

it means only that here are conceptions and a figuring imagination

strange to the Western intelligence. The line and run and turn demanded

by the Indian aesthetic sense are not the same as those demanded

by the European. It would take too long to examine the detail of

the difference which we find not only in sculpture, but in the other

plastic arts and in music and even to a certain extent in literature,

but on the whole we may say that the Indian mind moves on the spur

of a spiritual sensitiveness and psychic curiosity, while the aesthetic

curiosity of the European temperament is intellectual, vital, emotional

and imaginative in that sense, and almost the whole strangeness

of the Indian use of line and mass, ornament and proportion and

rhythm arises from this difference. The two minds live almost in

different worlds, are either not looking at the same things or,

even where they meet in the object, see it from a different level

or surrounded by a different atmosphere, and we know what power

the point of view or the medium of vision has to transform the object.

And undoubtedly there is very ample ground for Mr. Archer's complaint

of the want of naturalism in most Indian sculpture. The inspiration,

the way of seeing is frankly not naturalistic, not, that is to say,

the vivid, convincing and accurate, the graceful, beautiful or strong,

or even the idealised or imaginative imitation of surface or terrestrial

nature. The Indian sculptor is concerned with embodying spiritual

experiences and impressions, not with recording or glorifying what

is received by the physical senses. He may start with suggestions

from earthly and physical things, but he produces his work only

after he has closed his eyes to the Page 293 insistence of the physical

circumstances, seen them in the psychic memory and transformed them

within himself so as to bring out something other than their physical

reality or their vital and intellectual significance. His eye sees

the psychic line and turn of things and he replaces by them the

material contours. It is not surprising that such a method should

produce results which are strange to the average Western mind and

eye when these are not liberated by a broad and sympathetic culture.

And what is strange to us, is naturally repugnant to our habitual

mind and uncouth to our habitual sense, bizarre to our imaginative

tradition and aesthetic training. We want what is familiar to the

eye and obvious to the imagination and will not readily admit that

there may be here another and perhaps greater beauty than that in

the circle of which we are accustomed to live and take pleasure.

It seems to be especially the application of this psychic vision

to the human form which offends these critics of Indian sculpture.

There is the familiar objection to such features as the multiplication

of the arms in the figures of gods and goddesses, the four, six,

eight or ten arms of Shiva, the eighteen arms of Durga, because

they are a monstrosity, a thing not in nature. Now certainly a play

of imagination of this kind would be out of place in the representation

of a man or woman, because it would have no artistic or other meaning,

but I cannot see why this freedom should be denied in the representation

of cosmic beings like the Indian godheads. The whole question is,

first, whether it is an appropriate means of conveying a significance

not otherwise to be represented with an equal power and force and,

secondly, whether it is capable of artistic representation, a rhythm

of artistic truth and unity which need not be that of physical nature.

If not, then it is an ugliness and violence, but if these conditions

are satisfied, the means are justified and I do not see that we

have any right, faced with the perfection of the work, to raise

a discordant clamour. Mr. Archer himself is struck with the perfection

of skill and mastery with which these to him superfluous limbs are

disposed in the figures of the dancing Shiva, and indeed it would

need an eye of impossible blindness not to see that much, but what

is still more important is the artistic significance which this

skill is used to serve, and, if that is understood, we can at once

see that the spiritual emotion and suggestions of the cosmic dance

are brought out by this device in a way which would not be as possible

with a two-armed figure. The same truth holds as to the Durga with

her eighteen arms slaying the Asuras or the Shivas of the great

Pallava creations where the lyrical beauty of the Natarajas is absent,

but there is instead a great epical rhythm and grandeur. Art justifies

its own means and here it does it with a supreme perfection. And

as for the “contorted” postures of some figures, the same law holds.

There is often a departure in this respect from the anatomical norm

of the physical body or else—and that is a rather different thing—an

emphasis more or less pronounced on an unusual pose of limbs or

body, and the question then is whether it is done without sense

or purpose, a mere clumsiness or an ugly exaggeration, or whether

it rather serves some significance and establishes in the place

of the normal physical metric of Nature another purposeful and successful

artistic rhythm. Art after all is not forbidden to deal with the

unusual or to alter and overpass Nature, and it might almost be

said that it has been doing little else since it began to serve

the human imagination from its first grand epic exaggerations to

the violences of modern romanticism and realism, from the high ages

of Valmiki and Homer to the day of Hugo and Ibsen. The means matter,

but less than the significance and the thing done and the power

and beauty with which it expresses the dreams and truths of the

human spirit.

The whole question of the Indian artistic treatment of the human

figure has to be understood in the light of its aesthetic purpose.

It works with a certain intention and ideal, a general norm and

standard which permits of a good many variations and from which

too there are appropriate departures. The epithets with which Mr.

Archer tries to damn its features are absurd, captious, exaggerated,

the forced phrases of a journalist trying to depreciate a perfectly

sensible, beautiful and aesthetic norm with which he does not sympathise.

There are other things here than a repetition of hawk faces, wasp

waists, thin legs and the rest of the ill-tempered caricature. He

doubts Mr. Havell's suggestion that these old Indian artists knew

the anatomy of the body well enough, as Indian science knew it,

but chose to depart from it for their own purpose. It does not seem

to me to matter much, since art is not anatomy, nor an artistic

masterpiece necessarily a reproduction of physical fact or a lesson

in natural science. I see no reason to regret the absence of telling

studies in muscles, torsos, etc., for I cannot regard these things

as having in themselves any essential artistic value. The one important

point is that the Indian artist had a perfect idea of proportion

and rhythm and used them in certain styles with nobility and power,

in others like the Javan, the Gauda or the southern bronzes with

that or with a perfect grace added and often an intense and a lyrical

sweetness. The dignity and beauty of the human figure in the best

Indian statues cannot be excelled, but what was sought and what

was achieved was not an outward naturalistic, but a spiritual and

a psychic beauty, and to achieve it the sculptor suppressed, and

was entirely right in suppressing, the obtrusive material detail

and aimed instead at purity of outline and fineness of feature.

And into that outline, into that purity and fineness he was able

to work whatever he chose, mass of force or delicacy of grace, a

static dignity or a mighty strength or a restrained violence of

movement or whatever served or helped his meaning. A divine and

subtle body was his ideal; and to a taste and imagination too blunt

or realistic to conceive the truth and beauty of his idea, the ideal

itself may well be a stumbling-block, a thing of offence. But the

triumphs of art are not to be limited by the narrow prejudices of

the natural realistic man; that triumphs and endures which appeals

to the best, sadhu-sammatam, that is deepest and greatest which

satisfies the profoundest souls and the most sensitive psychic imaginations.

Each manner of art has its own ideals, traditions, agreed conventions;

for the ideas and forms of the creative spirit are many, though

there is one ultimate basis. The perspective, the psychic vision

of the Chinese and Japanese painters are not the same as those of

European artists; but who can ignore the beauty and the wonder of

their work? I dare say Mr. Archer would set a Constable or a Turner

above the whole mass of Far Eastern work, as I myself, if I had

to make a choice, would take a Chinese or Japanese landscape or

other magic transmutation of Nature in preference to all others;

but these are matters of individual, national or continental temperament

and preference. The essence of the question lies in the rendering

of the truth and beauty seized by the spirit. Indian sculpture,

Indian art in general follows its own ideal and traditions and these

are unique in their character and quality. It is the expression

great as a whole through many centuries and ages of creation, supreme

at its best, whether in rare early pre-Asokan, in Asokan or later

work of the first heroic age or in the magnificent statues of the

cave-cathedrals and Pallava and other southern temples or the noble,

accomplished or gracious imaginations of Bengal, Nepal and Java

through the after centuries or in the singular skill and delicacy

of the bronze work of the southern religions, a self-expression

of the spirit and ideals of a great nation and a great culture which

stands apart in the cast of its mind and qualities among the earth's

peoples, famed for its spiritual achievement, its deep philosophies

and its religious spirit, its artistic taste, the richness of its

poetic imagination, and not inferior once in its dealings with life

and its social endeavour and political institutions. This sculpture

is a singularly powerful, a seizing and profound interpretation

in stone and bronze of the inner soul of that people. The nation,

the culture failed for a time in life after a long greatness, as

others failed before it and others will yet fail that now flourish;

the creations of its mind have been arrested, this art like others

has ceased or fallen into decay, but the thing from which it rose,

the spiritual fire within still burns and in the renascence that

is coming it may be that this great art too will revive, not saddled

with the grave limitations of modern Western work in the kind, but

vivified by the nobility of a new impulse and power of the ancient

spiritual motive. Let it recover, not limited by old forms, but

undeterred by the cavillings of an alien mind, the sense of the

grandeur and beauty and the inner significance of its past achievement;

for in the continuity of its spiritual endeavour lies its best hope

for the future.

Footnote:

For example, one still reads with a sense of despairing stupefaction

“criticism” that speaks of Ravi Varma and Abanindranath Tagore as

artistic creators of different styles, but an equal power and genius!

All

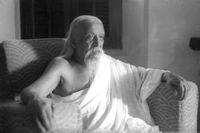

extracts and quotations from the written works of Sri Aurobindo

and the Mother and the Photographs of the Mother and Sri Aurobindo

are copyright Sri Aurobindo Trust, Pondicherry -605002 India

http://www.searchforlight.org

|