| |

The art of painting in ancient and later India, owing to the comparative

scantiness of its surviving creations, does not create quite so

great an impression as her architecture and sculpture and it has

even been supposed that this art flourished only at intervals, finally

ceased for a period of several centuries and was revived later on

by the Moguls and by Hindu artists who underwent the Mogul influence.

This however is a hasty view that does not outlast a more careful

research and consideration of the available evidence. It appears,

on the contrary, that Indian culture was able to arrive at a well

developed and an understanding aesthetic use of colour and line

from very early times and, allowing for the successive fluctuations,

periods of decline and fresh outbursts of originality and vigour,

which the collective human mind undergoes in all countries, used

this form of self-expression very persistently through the long

centuries of its growth and greatness. And especially it is apparent

now that there was a persistent tradition, a fundamental spirit

and turn of the aesthetic sense native to the mind of India which

links even the latest Rajput art to the earliest surviving work

still preserved at its highest summit of achievement in the rock-cut

retreats of Ajanta.

The materials of the art of painting are unfortunately more perishable

than those of any other of the greater means of creative aesthetic

self-expression and of the ancient masterpieces only a little survives,

but that little still indicates the immensity of the amount of work

of which it is the fading remnant. It is said that of the twenty-nine

caves at Ajanta almost all once bore signs of decoration by frescoes;

only so long ago as forty years sixteen still contained something

of the original paintings, but now six alone still bear their witness

to the greatness of this ancient art, though rapidly perishing and

deprived of something of the original warmth and beauty and glory

of colour. The rest of all that vivid contemporaneous creation which

must at one time have covered the whole country in the temples and

viharas and the houses of the cultured and the courts and pleasure-houses

of nobles and kings, has perished, and we have only, more or less

similar to the work at Ajanta, some crumbling fragments of rich

and profuse decoration in the caves of Bagh and a few paintings

of female figures in two rock-cut chambers at Sigiriya.*

These remnants represent the work of some six or seven centuries,

but they leave gaps, and nothing now remains of any paintings earlier

than the first century of the Christian era, except some frescoes,

spoilt by unskilful restoration, from the first century before it,

while after the seventh there is a blank which might at first sight

argue a total decline of the art, a cessation and disappearance.

But there are fortunately evidences which carry back the tradition

of the art at one end many centuries earlier and other remains more

recently discovered and of another kind outside India and in the

Himalayan countries carry it forward at the other end as late as

the twelfth century and help us to link it on to the later schools

of Rajput painting. The history of the self-expression of the Indian

mind in painting covers a period of as much as two millenniums of

more or less intense artistic creation and stands on a par in this

respect with the architecture and sculpture.

The paintings that remain to us from ancient times are the work

of Buddhist painters, but the art itself in India was of pre-Buddhistic

origin. The Tibetan historian ascribes a remote antiquity to all

the crafts, prior to the Buddha, and this is a conclusion increasingly

pointed to by a constant accumulation of evidence. Already in the

third century before the Christian era we find the theory of the

art well founded from previous times, the six essential elements,

sadanga, recognised and enumerated, like the more or less corresponding

six Chinese canons which are first mentioned nearly a thousand years

later, and in a very ancient work on the art pointing back to pre-Buddhistic

times a number of careful and very well-defined rules and traditions

are laid down which were developed into an elaborate science of

technique and traditional rule in the later Shilpasutras. The frequent

references in the ancient literature also are of a character which

would have been impossible without a widespread practice and appreciation

of the art by both men and women of the cultured classes, and these

allusions and incidents evidencing a moved delight in the painted

form and beauty of colour and the appeal both to the decorative

sense and to the aesthetic emotion occur not only in the later poetry

of Kalidasa, Bhavabhuti and other classical dramatists, but in the

early popular drama of Bhasa and earlier still in the epics and

in the sacred books of the Buddhists. The absence of any actual

creations of this earlier art makes it indeed impossible to say

with absolute certainty what was its fundamental character and intimate

source of inspiration or whether it was religious and hieratic or

secular in its origin. The theory has been advanced rather too positively

that it was in the courts of kings that the art began and with a

purely secular motive and inspiration, and it is true that while

the surviving work of Buddhist artists is mainly religious in subject

or at least links on common scenes of life to Buddhist ceremony

and legend, the references in the epic and dramatic literature are

usually to painting of a more purely aesthetic character, personal,

domestic or civic, portrait painting, the representation of scenes

and incidents in the lives of kings and other great personalities

or mural decoration of palaces and private or public buildings.

On the other hand, there are similar elements in Buddhist painting,

as, for example, the portraits of the queens of King Kashyapa at

Sigiriya, the historic representation of a Persian embassy or the

landing of Vijaya in Ceylon. And we may fairly assume that all along

Indian painting both Buddhist and Hindu covered much the same kind

of ground as the later Rajput work in a more ample fashion and with

a more antique greatness of spirit and was in its ensemble an interpretation

of the whole religion, culture and life of the Indian people. The

one important and significant thing that emerges is the constant

oneness and continuity of all Indian art in its essential spirit

and tradition. Thus the earlier work at Ajanta has been found to

be akin to the earlier sculptural work of the Buddhists, while the

later paintings have a similar close kinship to the sculptural reliefs

at Java. And we find that the spirit and tradition which reigns

through all changes of style and manner at Ajanta, is present too

at Bagh and Sigiriya, in the Khotan frescoes, in the illuminations

of Buddhist manuscripts of a much later time and in spite of the

change of form and manner is still spiritually the same in the Rajput

paintings. This unity and continuity enable us to distinguish and

arrive at a clear understanding of what is the essential aim, inner

turn and motive, spiritual method which differentiate Indian painting

first from occidental work and then from the nearer and more kindred

art of other countries of Asia.

The spirit and motive of Indian painting are in their centre of

conception and shaping force of sight identical with the inspiring

vision of Indian sculpture. All Indian art is a throwing out of

a certain profound self-vision formed by a going within to find

out the secret significance of form and appearance, a discovery

of the subject in one's deeper self, the giving of soul-form to

that vision and a remoulding of the material and natural shape to

express the psychic truth of it with the greatest possible purity

and power of outline and the greatest possible concentrated rhythmic

unity of significance in all the parts of an indivisible artistic

whole. Take whatever masterpiece of Indian painting and we shall

find these conditions aimed at and brought out into a triumphant

beauty of suggestion and execution. The only difference from the

other arts comes from the turn natural and inevitable to its own

kind of aesthesis, from the moved and indulgent dwelling on what

one might call the mobilities of the soul rather than on its static

eternities, on the casting out of self into the grace and movement

of psychic and vital life (subject always to the reserve and restraint

necessary to all art) rather than on the holding back of life in

the stabilities of the self and its eternal qualities and principles,

guna and tattwa. This distinction is of the very essence of the

difference between the work given to the sculptor and the painter,

a difference imposed on them by the natural scope, turn, possibility

of their instrument and medium. The sculptor must express always

in static form; the idea of the spirit is cut out for him in mass

and line, significant in the stability of its insistence, and he

can lighten the weight of this insistence but not get rid of it

or away from it; for him eternity seizes hold of time in its shapes

and arrests it in the monumental spirit of stone or bronze. The

painter on the contrary lavishes his soul in colour and there is

a liquidity in the form, a fluent grace of subtlety in the line

he uses which imposes on him a more mobile and emotional way of

self-expression. The more he gives us of the colour and changing

form and emotion of the life of the soul, the more his work glows

with beauty, masters the inner aesthetic sense and opens it to the

thing his art better gives us than any other, the delight of the

motion of the self out into a spiritually sensuous joy of beautiful

shapes and the coloured radiances of existence. Painting is naturally

the most sensuous of the arts, and the highest greatness open to

the painter is to spiritualise this sensuous appeal by making the

most vivid outward beauty a revelation of subtle spiritual emotion

so that the soul and the sense are at harmony in the deepest and

finest richness of both and united in their satisfied consonant

expression of the inner significances of things and life. There

is less of the austerity of Tapasya in his way of working, a less

severely restrained expression of eternal things and of the fundamental

truths behind the forms of things, but there is in compensation

a moved wealth of psychic or warmth of vital suggestion, a lavish

delight of the beauty of the play of the eternal in the moments

of time and there the artist arrests it for us and makes moments

of the life of the soul reflected in form of man or creature or

incident or scene or Nature full of a permanent and opulent significance

to our spiritual vision. The art of the painter justifies visually

to the spirit the search of the sense for delight by making it its

own search for the pure intensities of meaning of the universal

beauty it has revealed or hidden in creation; the indulgence of

the eye's desire in perfection of form and colour becomes an enlightenment

of the inner being through the power of a certain spiritually aesthetic

Ananda.

The Indian artist lived in the light of an inspiration which imposed

this greater aim on his art and his method sprang from its fountains

and served it to the exclusion of any more earthly sensuous or outwardly

imaginative aesthetic impulse. The six limbs of his art, the sadanga,

are common to all work in line and colour: they are the necessary

elements and in their elements the great arts are the same everywhere;

the distinction of forms, rupabheda, proportion, arrangement

of line and mass, design, harmony, perspective, pramana,

the emotion or aesthetic feeling expressed by the form, bhava,

the seeking for beauty and charm for the satisfaction of the aesthetic

spirit, lavanya, truth of the form and its suggestion, sadrsya,

the turn, combination, harmony of colours, varnikabhanga,

are the first constituents to which every successful work of art

reduces itself in analysis. But it is the turn given to each of

the constituents which makes all the difference in the aim and effect

of the technique and the source and character of the inner vision

guiding the creative hand in their combination which makes all the

difference in the spiritual value of the achievement, and the unique

character of Indian painting, the peculiar appeal of the art of

Ajanta springs from the remarkably inward, spiritual and psychic

turn which was given to the artistic conception and method by the

pervading genius of Indian culture. Indian painting no more than

Indian architecture and sculpture could escape from its absorbing

motive, its transmuting atmosphere, the direct or subtle obsession

of the mind that has been subtly and strangely changed, the eye

that has been trained to see, not as others with only the external

eye but by a constant communing of the mental parts and the inner

vision with the self beyond mind and the spirit to which forms are

only a transparent veil or a slight index of its own greater splendour.

The outward beauty and power, the grandeur of drawing, the richness

of colour, the aesthetic grace of this painting is too obvious and

insistent to be denied, the psychical appeal usually carries something

in it to which there is a response in every cultivated and sensitive

human mind and the departures from the outward physical norm are

less vehement and intense, less disdainful of the more external

beauty and grace,—as is only right in the nature of this art,—than

in the sculpture: therefore we find it more easily appreciated up

to a certain point by the Western critical mind, and even when not

well appreciated, it is exposed to milder objections. There is not

the same blank incomprehension or violence of misunderstanding and

repulsion. And yet we find at the same time that there is something

which seems to escape the appreciation or is only imperfectly understood,

and this something is precisely that profounder spiritual intention

of which the things the eye and aesthetic sense immediately seize

are only the intermediaries. This explains the remark often made

about Indian work of the less visibly potent and quieter kind that

it lacks inspiration or imagination or is a conventional art: the

spirit is missed where it does not strongly impose itself, and is

not fully caught even where the power which is put into the expression

is too great and direct to allow of denial. Indian painting like

Indian architecture and sculpture appeals through the physical and

psychical to another spiritual vision from which the artist worked

and it is only when this is no less awakened in us than the aesthetic

sense that it can be appreciated in all the depth of its significance.

The orthodox Western artist works by a severely conscientious reproduction

of the forms of outward Nature; the external world is his model,

and he has to keep it before his eye and repress any tendency towards

a substantial departure from it or any motion to yield his first

allegiance to a subtler spirit. His imagination submits itself to

physical Nature even when he brings in conceptions which are more

properly of another kingdom, the stress of the physical world is

always with him, and the Seer of the subtle, the creator of mental

forms, the inner Artist, the wide-eyed voyager in the vaster psychical

realms, is obliged to subdue his inspirations to the law of the

Seer of the outward, the spirit that has embodied itself in the

creations of the terrestrial life, the material universe. An idealised

imaginative realism is as far as he can ordinarily go in the method

of his work when he would fill the outward with the subtler inner

seeing. And when, dissatisfied with this confining law, he would

break quite out of the circle, he is exposed to a temptation to

stray into intellectual or imaginative extravagances which violate

the universal rule of the right distinction of forms, rupabheda,

and belong to the vision of some intermediate world of sheer fantasia.

His art has discovered the rule of proportion, arrangement and perspective

which preserves the illusion of physical Nature and he relates his

whole design to her design in a spirit of conscientious obedience

and faithful dependence. His imagination is a servant or interpreter

of her imaginations, he finds in the observation of her universal

law of beauty his secret of unity and harmony and his subjectivity

tries to discover itself in hers by a close dwelling on the objective

shapes she has given to her creative spirit. The farthest he has

got in the direction of a more intimately subjective spirit is an

impressionism which still waits upon her models but seeks to get

at some first inward or original effect of them on the inner sense,

and through that he arrives at some more strongly psychical rendering,

but he does not work altogether from within outward in the freer

manner of the oriental artist. His emotion and artistic feeling

move in this form and are limited by this artistic convention and

are not a pure spiritual or psychic emotion but usually an imaginative

exaltation derived from the suggestions of life and outward things

with a psychic element or an evocation of spiritual feeling initiated

and dominated by the touch of the outward. The charm that he gives

is a sublimation of the beauty that appeals to the outward senses

by the power of the idea and the imagination working on the outward

sense appeal and other beauty is only brought in by association

into that frame. The truth of correspondence he depends upon is

a likeness to the creations of physical Nature and their intellectual,

emotional and aesthetic significances, and his work of line and

wave of colour are meant to embody the flow of this vision. The

method of this art is always a transcript from the visible world

with such necessary transmutation as the aesthetic mind imposes

on its materials. At the lowest to illustrate, at the highest to

interpret life and Nature to the mind by identifying it with deeper

things through some derivative touch of the spirit that has entered

into and subdued itself to their shapes, pravisya yah pratirupo

babhuva, is the governing principle.**

The Indian artist sets out from the other end of the scale of values

of experience which connect life and the spirit. The whole creative

force comes here from a spiritual and psychic vision, the emphasis

of the physical is secondary and always deliberately lightened so

as to give an overwhelmingly spiritual and psychic impression and

everything is suppressed which does not serve this purpose or would

distract the mind from the purity of this intention. This painting

expresses the soul through life, but life is only a means of the

spiritual self-expression, and its outward representation is not

the first object or the direct motive. There is a real and a very

vivid and vital representation, but it is more of an inner psychical

than of the outward physical life. A critic of high repute speaking

of the Indian influence in a famous Japanese painting fixes on the

grand strongly outlined figures and the feeling for life and character

recalling the Ajanta frescoes as the signs of its Indian character:

but we have to mark carefully the nature of this feeling for life

and the origin and intention of this strong outlining of the figures.

The feeling for life and character here is a very different thing

from the splendid and abundant vitality and the power and force

of character which we find in an Italian painting, a fresco from

Michael Angelo's hand or a portrait by Titian or Tintoretto. The

first primitive object of the art of painting is to illustrate life

and Nature and at the lowest this becomes a more or less vigorous

and original or conventionally faithful reproduction, but it rises

in great hands to a revelation of the glory and beauty of the sensuous

appeal of life or of the dramatic power and moving interest of character

and emotion and action. That is a common form of aesthetic work

in Europe; but in Indian art it is never the governing motive. The

sensuous appeal is there, but it is refined into only one and not

the chief element of the richness of a soul of psychic grace and

beauty which is for the Indian Page 306 artist the true beauty,

lavanya: the dramatic motive is subordinated and made only

a purely secondary element, only so much is given of character and

action as will help to bring out the deeper spiritual or psychic

feeling, bhava, and all insistence or too prominent force

of these more outwardly dynamic things is shunned, because that

would externalise too much the spiritual emotion and take away from

its intense purity by the interference of the grosser intensity

which emotion puts on in the stress of the active outward nature.

The life depicted is the life of the soul and not, except as a form

and a helping suggestion, the life of the vital being and the body.

For the second more elevated aim of art is the interpretation or

intuitive revelation of existence through the forms of life and

Nature and it is this that is the starting-point of the Indian motive.

But the interpretation may proceed on the basis of the forms already

given us by physical Nature and try to evoke by the form an idea,

a truth of the spirit which starts from it as a suggestion and returns

upon it for support, and the effort is then to correlate the form

as it is to the physical eye with the truth which it evokes without

overpassing the limits imposed by the appearance. This is the common

method of occidental art always zealous for the immediate fidelity

to Nature which is its idea of true correspondence, sadrsya,

but it is rejected by the Indian artist. He begins from within,

sees in his soul the thing he wishes to express or interpret and

tries to discover the right line, colour and design of his intuition

which, when it appears on the physical ground, is not a just and

reminding reproduction of the line, colour and design of physical

nature, but much rather what seems to us a psychical transmutation

of the natural figure. In reality the shapes he paints are the forms

of things as he has seen them in the psychical plane of experience:

these are the soul-figures of which physical things are a gross

representation and their purity and subtlety reveals at once what

the physical masks by the thickness of its casings. The lines and

colours sought here are the psychic lines and the psychic hues proper

to the vision which the artist has gone into himself to discover.

This is the whole governing principle of the art which gives its

stamp to every detail of an Indian painting and transforms the artist's

use of the six limbs of the canon. The distinction of forms is faithfully

observed, but not in the sense of an exact naturalistic fidelity

to the physical appearance with the object of a faithful reproduction

of the outward shapes of the world in which we live. To recall with

fidelity something our eyes have seen or could have seen on the

spot, a scene, an interior, a living and breathing person, and give

the aesthetic sense and emotion of it to the mind is not the motive.

There is here an extraordinary vividness, naturalness, reality,

but it is a more than physical reality, a reality which the soul

at once recognises as of its own sphere, a vivid naturalness of

psychic truth, the convincing spirit of the form to which the soul,

not the outward naturalness of the form to which the physical eye

bears witness. The truth, the exact likeness is there, the correspondence,

sadrsya, but it is the truth of the essence of the form,

it is the likeness of the soul to itself, the reproduction of the

subtle embodiment which is the basis of the physical embodiment,

the purer and finer subtle body of an object which is the very expression

of its own essential nature, svabhava. The means by which

this effect is produced is characteristic of the inward vision of

the Indian mind. It is done by a bold and firm insistence on the

pure and strong outline and a total suppression of everything that

would interfere with its boldness, strength and purity or would

blur over and dilute the intense significance of the line. In the

treatment of the human figure all corporeal filling in of the outline

by insistence on the flesh, the muscle, the anatomical detail is

minimised or disregarded: the strong subtle lines and pure shapes

which make the humanity of the human form are alone brought into

relief; the whole essential human being is there, the divinity that

has taken this garb of the spirit to the eye, but not the superfluous

physicality which he carries with him as his burden. It is the ideal

psychical figure and body of man and woman that is before us in

its charm and beauty. The filling in of the line is done in another

way; it is effected by a disposition of pure masses, a design and

coloured wave-flow of the body, bhanga, a simplicity of content

that enables the artist to flood the whole with the significance

of the one spiritual emotion, feeling, suggestion which he intends

to convey, his intuition of the moment of the soul, its living self-experience.

All is disposed so as to express that and that alone. The almost

miraculously subtle and meaningful use of the hands to express the

psychic suggestion is a common and well-marked feature of Indian

paintings and the way in which the suggestion of the face and the

eyes is subtly repeated or supplemented by this expression of the

hands is always one of the first things that strikes the regard,

but as we continue to look, we see that every turn of the body,

the pose of each limb, the relation and design of all the masses

are filled with the same psychical feeling. The more important accessories

help it by a kindred suggestion or bring it out by a support or

variation or extension or relief of the motive. The same law of

significant line and suppression of distracting detail is applied

to animal forms, buildings, trees, objects. There is in all the

art an inspired harmony of conception, method and expression. Colour

too is used as a means for the spiritual and psychic intention,

and we can see this well enough if we study the suggestive significance

of the hues in a Buddhist miniature. This power of line and subtlety

of psychic suggestion in the filling in of the expressive outlines

is the source of that remarkable union of greatness and moving grace

which is the stamp of the whole work of Ajanta and continues in

Rajput painting, though there the grandeur of the earlier work is

lost in the grace and replaced by a delicately intense but still

bold and decisive power of vivid and suggestive line. It is this

common spirit and tradition which is the mark of all the truly indigenous

work of India.

These things have to be carefully understood and held in mind when

we look at an Indian painting and the real spirit of it first grasped

before we condemn or praise. To dwell on that in it which is common

to all art is well enough, but it is what is peculiar to India that

is its real essence. And there again to appreciate the technique

and the fervour of religious feeling is not sufficient; the spiritual

intention served by the technique, the psychic significance of line

and colour, the greater thing of which the religious emotion is

the result has to be felt if we would identify ourself with the

whole purpose of the artist. If Page 309 we look long, for an example,

at the adoration group of the mother and child before the Buddha,

one of the most profound, tender and noble of the Ajanta masterpieces,

we shall find that the impression of intense religious feeling of

adoration there is only the most outward general touch in the ensemble

of the emotion. That which it deepens to is the turning of the soul

of humanity in love to the benignant and calm Ineffable which has

made itself sensible and human to us in the universal compassion

of the Buddha, and the motive of the soul moment the painting interprets

is the dedication of the awakening mind of the child, the coming

younger humanity, to that in which already the soul of the mother

has learned to find and fix its spiritual joy.

The eyes, brows, lips, face, poise of the head of the woman are

filled with this spiritual emotion which is a continued memory and

possession of the psychical release, the steady settled calm of

the heart's experience filled with an ineffable tenderness, the

familiar depths which are yet moved with the wonder and always farther

appeal of something that is infinite, the body and other limbs are

grave masses of this emotion and in their poise a basic embodiment

of it, while the hands prolong it in the dedicative putting forward

of her child to meet the Eternal. This contact of the human and

eternal is repeated in the smaller figure with a subtly and strongly

indicated variation, the glad and childlike smile of awakening which

promises but not yet possesses the depths that are to come, the

hands disposed to receive and keep, the body in its looser curves

and waves harmonising with that significance. The two have forgotten

themselves and seem almost to forget or confound each other in that

which they adore and contemplate, and yet the dedicating hands unite

mother and child in the common act and feeling by their simultaneous

gesture of maternal possession and spiritual giving. The two figures

have at each point the same rhythm, but with a significant difference.

The simplicity in the greatness and power, the fullness of expression

gained by reserve and suppression and concentration which we find

here is the perfect method of the classical art of India. And by

this perfection Buddhist art became not merely an illustration of

the religion and an expression of its thought and its religious

feeling, history and legend, but a revealing interpretation of the

spiritual sense of Buddhism and its profounder meaning to the soul

of India.

To understand that—we must always seek first and foremost this kind

of deeper intention—is to understand the reason of the differences

between the occidental and the Indian treatment of the life motives.

Thus a portrait by a great European painter will express with sovereign

power the soul through character, through the active qualities,

the ruling powers and passions, the master feeling and temperament,

the active mental and vital man: the Indian artist tones down the

outward-going dynamic indices and gives only so much of them as

will serve to bring out or to modulate something that is more of

the grain of the subtle soul, something more static and impersonal

of which our personality is at once the mask and the index. A moment

of the spirit expressing with purity the permanence of a very subtle

soul quality is the highest type of the Indian portrait. And more

generally the feeling for character which has been noted as a feature

of the Ajanta work is of a similar kind. An Indian painting expressing,

let us say, a religious feeling centred on some significant incident

will show the expression in each figure varied in such a way as

to bring out the universal spiritual essence of the emotion modified

by the essential soul type, different waves of the one sea, all

complexity of dramatic insistence is avoided, and so much stress

only is laid on character in the individual feeling as to give the

variation without diminishing the unity of the fundamental emotion.

The vividness of life in these paintings must not obscure for us

the more profound purpose for which it is the setting, and this

has especially to be kept in mind in our view of the later art which

has not the greatness of the classic work and runs to a less grave

and highly sustained kind, to lyric emotion, minute vividness of

life movement, the more naive feelings of the people. One sometimes

finds inspiration, decisive power of thought and feeling, originality

of creative imagination denied to this later art; but its real difference

from that of Ajanta is only that the intermediate psychic transmission

between the life movement and the inmost motive has been given Page

311 with less power and distinctness: the psychic thought and feeling

are there more thrown outward in movement, less contained in the

soul, but still the soul motive is not only present but makes the

true atmosphere and if we miss it, we miss the real sense of the

picture. This is more evident where the inspiration is religious,

but it is not absent from the secular subject. Here too spiritual

intention or psychic suggestion are the things of the first importance.

In Ajanta work they are all-important and to ignore them at all

is to open the way to serious errors of interpretation. Thus a highly

competent and very sympathetic critic speaking of the painting of

the Great Renunciation says truly that this great work excels in

its expression of sorrow and feeling of profound pity, but then,

looking for what a Western imagination would naturally put into

such a subject, he goes on to speak of the weight of a tragic decision,

the bitterness of renouncing a life of bliss blended with a yearning

sense of hope in the happiness of the future, and that is singularly

to misunderstand the spirit in which the Indian mind turns from

the transient to the eternal, to mistake the Indian art motive and

to put a vital into the place of a spiritual emotion. It is not

at all his own personal sorrow but the sorrow of all others, not

an emotional self-pity but a poignant pity for the world, not the

regret for a life of domestic bliss but the afflicting sense of

the unreality of human happiness that is concentrated in the eyes

and lips of the Buddha, and the yearning there is not, certainly,

for earthly happiness in the future but for the spiritual way out,

the anguished seeking which found its release, already foreseen

by the spirit behind and hence the immense calm and restraint that

support the sorrow, in the true bliss of Nirvana. There is illustrated

the whole difference between two kinds of imagination, the mental,

vital and physical stress of the art of Europe and the subtle, less

forcefully tangible spiritual stress of the art of India.

It is the indigenous art of which this is the constant spirit and

tradition, and it has been doubted whether the Mogul paintings deserve

that name, have anything to do with that tradition and are not rather

an exotic importation from Persia. Almost all oriental art is akin

in this respect that the psychic enters into and for the most part

lays its subtler law on the physical vision and the psychic line

and significance give the characteristic turn, are the secret of

the decorative skill, direct the higher art in its principal motive.

But there is a difference between the Persian psychicality which

is redolent of the magic of the middle worlds and the Indian which

is only a means of transmission of the spiritual vision. And obviously

the Indo-Persian style is of the former kind and not indigenous

to India. But the Mogul school is not an exotic; there is rather

a blending of two mentalities: on the one side there is a leaning

to some kind of externalism which is not the same thing as Western

naturalism, a secular spirit and certain prominent elements that

are more strongly illustrative than interpretative, but the central

thing is still the domination of a transforming touch which shows

that there as in the architecture the Indian mind has taken hold

of another invading mentality and made it a help to a more outward-going

self-expression that comes in as a new side strain in the spiritual

continuity of achievement which began in prehistoric times and ended

only with the general decline of Indian culture. Painting, the last

of the arts in that decline to touch the bottom, has also been the

first to rise again and lift the dawn fires of an era of new creation.

It is not necessary to dilate on the decorative arts and crafts

of India, for their excellence has always been beyond dispute. The

generalised sense of beauty which they imply is one of the greatest

proofs that there can be of the value and soundness of a national

culture. Indian culture in this respect need not fear any comparison:

if it is less predominantly artistic than that of Japan, it is because

it has put first the spiritual need and made all other things subservient

to and a means for the spiritual growth of the people. Its civilisation,

standing in the first rank in the three great arts as in all things

of the mind, has proved that the spiritual urge is not, as has been

vainly supposed, sterilising to the other activities, but a most

powerful force for the many-sided development of the human whole.

*: Since then more paintings

of high quality have been found in some southern temples, akin in

their spirit and style to the work at Ajanta.

**:

All this is no longer true of European art in much of its more prominent

recent developments.

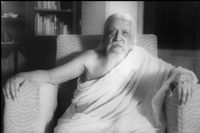

All

extracts and quotations from the written works of Sri Aurobindo

and the Mother and the Photographs of the Mother and Sri Aurobindo

are copyright Sri Aurobindo Trust, Pondicherry -605002 India

http://www.searchforlight.org

|